Car-parking policies to eliminate urban sprawl and revive buses

Car-parking policies to eliminate urban sprawl and revive buses (June 2025, published online, December 2025).

This guidance was produced in June 2025, following consultation by Alice Roberts at CPRE London (alice@cprelondon.org.uk). We have published more useful evidence on this subject here.

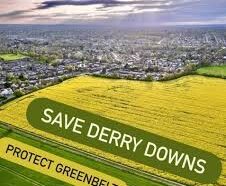

Most of our towns and cities have very large amounts of land given to surface car parking (see Parkulator) which could be used for housing. At the same time, new housing development is often built on green fields, away from the centre, in a way that requires more than one, sometimes more than two, car parking spaces per household. Ultimately this mixture of residential and destination parking undermines public transport.

Here we set out a series of policies which local councils may wish to consider, and which local campaigners may wish to promote (to be adopted in Local Plans, and Local Transport Plans) as they go about advocating against urban sprawl and for development which does not gobble up productive and beautiful countryside but instead is well-located within existing towns, or else on the urban fringe, which can be serviced by public transport, walking and cycling and which can even support delivery of affordable housing, where car parks are publicly owned. We emphasise the importance of parking policy to achieving these goals and particularly to improving public transport, especially bus services.[1] We suggest reading this alongside this presentation which sets out examples and images to better explain the issues and policies (click, scroll past opening paragraphs, see ‘Resources for Local Campaigners’).

Why parking matters

Availability of car-parking is a major determinant of travel mode and over-provision undermines the financial viability and attractiveness of public transport and active travel. Too much parking, especially low-cost parking, starts a negative feedback loop, reducing demand for public transport as more people drive, but also as bus service reliability and attractiveness falls due to rising traffic. This causes cuts to public transport, further undermining services, creating more traffic and pressure for more car-parking space. Those without access to a car have their opportunities reduced as their mobility is curtailed. Therefore, managing car-parking is essential to creating equitable places.

Health-positive, age-positive, equitable transport. Reducing car dependency has extensive positive social, environmental and economic impacts: increased activity levels; reduced emissions; reduced isolation for older people, people on low incomes and those with disabilities; increased independence for teenagers and older children; reduced road casualties; wider labour markets for employers and reduced absenteeism; increased footfall for retailers; more attractive settings, not least for historic buildings and town centres, all of which benefit the economy; reduced community severance; and equity for the many people who do not wish to, are not able to, or cannot afford to own or drive a car.

Local Transport Plans – policies to promote

Local Transport Plans need strong residential and destination parking policies to deliver incremental mode shift i.e. from car trips to public transport, walking, wheeling and cycling. Mode shift targets are fundamental to ‘vision based’ transport planning and should be ambitious and specific in relation to different modes.

Controlling parking Transport planners should work with planning, highways and parking teams to restrict, reduce and increase charges for car-parking (including considering introducing a Workplace Parking Levy), using any surplus income to improve people’s travel choices e.g. funding concessionary fares. See Local Authority Parking Finances in England 2023-24 (published March 2025) for comparative data on parking account surpluses.

Take advantage of bus franchising powers Use bus franchising powers to cross-subsidise profitable and non-profitable routes and use surplus from parking accounts to promote bus patronage e.g. by funding concessions or improving bus infrastructure.

Adopt ‘kerbside’ policy Transport, highways and parking teams should also work together to allocate a minimum of 25% of kerbside, as well as excess road space and road lanes, for active travel, public transport and green infrastructure.

- [Kerbside action and ‘road diets’ Roads (carriageway / kerbside) need to accommodate bus lanes, cycle lanes, cycle hangars and cycle visitor parking, wider pavements, loading bays to avoid dangerous parking, street trees (on build outs), rain gardens (to manage surface water run-off), Electric Vehicle charging points (on buildouts) and much more, to support delivery of walking, wheeling, cycling and public transport. At the same time, roads which have too many lanes induce traffic and cause more road casualties, making streets less safe and increasing pressure on the NHS. Car-parking (often free) induces traffic, while also using road space which could, if redeployed, support active and public transport, and green infrastructure.]

Local Plans – policies to promote

Local Plans should direct that new residential and mixed-use development should be planned to promote ‘compact’ towns and cities and deliver mode shift. Development should be located within or close to a town centre; built at density to support the financial viability of bus services; and be car-free or low-car.

The expected travel mode of new residents should be clear and Local Plan policy should direct that a high proportion of trips generated by new development should be made by public transport, walking, cycling or wheeling.

Density should be high enough to support public transport and low-car living. Evidence suggests a minimum of 62 dwellings per hectare [2] is needed to support financially-viable public transport but ‘gentle density’ of 100 or more is more effective at supporting public transport and local amenities and can be achieved with sympathetic, low-rise buildings and even terraced housing (see examples of various densities here and Annex 1 below, for 10 Reasons why higher density living is good for communities). Higher density is more land-efficient, a bigger range of shops and services that can be supported and, of most significance, the cost of personal transport diminishes rapidly as density increases. Better transport means better access to jobs, amenities, leisure, etc. At high densities fast, frequent, reliable public transport systems become fully effective with dramatic reductions in energy & costs. [3]

In relation to car-parking, Local Plans should contain a ‘zero car’ parking policy as the starting point for new development. Local Plans should specify car-parking maximums and introduce ‘zero car as a starting point’ (no parking space except disabled bays) or ‘car lite’ policy (e.g. 1 car-parking space to every 3 households plus disabled bays) or alternatively access to car club vehicles only. Examples from London, Oxford and Brighton are given towards the end of this presentation.

Local Plans should allocate Town Centre destination parking for development, also enabling affordable housing where car parks are council-owned. Car-parking is often substantially over-provisioned in town centres (see Parkulator). Local Plans should promote redevelopment of town-centre, surface car parks, multi-storey car parks, car-dependent retail sites and empty office blocks, for residential and mixed-use development. This will have multiple benefits, enabling new town centre housing (including affordable housing where and is owned by the council) while reducing car trips and supporting public transport.

Plans for town-centre improvements (in Local Plans) should be part of master-planning exercises, linked to reduction in car-parking and traffic, and a shift away from car-dependent, retail on the town periphery. Town centres, particularly those with historic settings, can be made more attractive by reducing car parking and traffic so that visitors and shoppers (evidence shows) will stay longer and spend more (see e.g. Pedestrian Pound).

Local Plans should support public transport, walking, cycling and wheeling by allocating space for bus transit, delivery hubs and cycle parking (and other key active and sustainable travel infrastructure). In relation to active travel and public transport, Local Plans should allocate space to support bus transit, low carbon delivery and cycling; and set out policies to support public transport, cycling / wheeling and walking, including via residential and destination cycle parking standards.

Local Plans should provide clarity for developers, particularly on low car-parking standards, to ensure local authorities can lever investment into public transport, walking and cycling. In ‘Stepping Off The Road To Nowhere’, Create Streets and Sustrans demonstrate that better quality, lower carbon, more attractive transport and development solutions can cost the same or less than the dominant road-centric model and be better for local businesses and the economy. Developers need clarity on expectations, not least on low car-parking standards, in order to deliver change.

Note on supportive national policy

National policy needs to support Local Authorities to put in place appropriate parking policies to promote better, financially-sustainable public transport. Government should:

- Introduce an NPPF policy promoting ‘low car’ development, including a presumption in favour of ‘zero car development as a starting point’ for housing and mixed-use development (but accommodating disabled parking needs and car clubs if necessary).

- Delete NPPF paragraphs 113 (presumption against parking maxima) and 112d (relevance of local car ownership levels). [4]

- Introduce an NPPF policy presumption in favour of redeveloping under-used, town-centre sites particularly surface car parks and single-storey, car-dependent retail sites like supermarkets and ‘big box’ retail, for new homes and other services. The redevelopment of multi-storey car parks could also be encouraged.

- Introduce ‘Grey Space’ policy into the NPPF to promote the redeployment of space currently allocated to roads and car-parking e.g. to accommodate recreation or play, sustainable drainage or building, trees and benches, recognising how this will also reduce traffic. Grey space takes up significant land in urban areas, with major negative impacts for transport and environment outcomes: its exclusion from spatial strategy undermines the ability of town planners to deliver effective place-making to improve the attractiveness of an area that will boost the economy as well as improving people’s quality of life. It also hampers a council’s ability to manage surface water, air temperature and quality, and biodiversity habitat.

Annex 1: Ten reasons why higher density living is positive for communities

- The higher the density, the more land is saved: space is used more efficiently.

- The higher the density, the bigger range of shops and services that can be supported. Of most significance is the cost of personal transport which diminishes rapidly as density increases.

- Better transport means better access to jobs, amenities, leisure, etc. At high densities fast, frequent, reliable public transport systems become fully effective with dramatic reductions in energy & costs.

- As density increases the per capita cost of providing services such as water, gas, electricity and waste disposal reduces.

- The cost of transporting materials and goods also declines. As the costs go down so does the consumption of energy.

- As density increases, isolation and social exclusion is reduced for people without a car.

- Density can also impact on affordability as the cost of land is lower per dwelling, and space is not needed for parking cars, for instance.

- Higher density creates more vitality and diversity. “Bigger concentrations of people stimulate and support the provision of more services and facilities making possible a wider choice of restaurants, theatres, cinemas and other recreational opportunities. They support specialist centres and services for minorities, which are not possible where such minorities are dispersed in low density sprawl. …

- “All this stimulates interdependent economic development that creates new employment opportunities and greater choice of employment.

- “Above all, in higher density urban areas, all this diversity is within easy reach of where most people live. Ease of access is a key factor, which has critical implications for a sustainable quality of urban life.”

NOTES

[1] This policy supplements CPRE Transport Policy 9 (Parking and Parking Standards) adopted in 2024.

[2] https://www.irbnet.de/daten/iconda/CIB919.pdf see page 149

[3] reference 2 and Annex 1 above (Ten reasons why higher density living is good for communities)

[4] Para 113. NPPF. “Maximum parking standards for residential and non-residential development should only be set where there is a clear and compelling justification that they are necessary for managing the local road network, or for optimising the density of development in city and town centres and other locations that are well served by public transport (in accordance with chapter 11 of this Framework). In town centres, local authorities should seek to improve the quality of parking so that it is convenient, safe and secure, alongside measures to promote accessibility for pedestrians and cyclists.” Para 112. NPPF. “If setting local parking standards for residential and non-residential development, policies should take into account: a) the accessibility of the development; b) the type, mix and use of development; c) the availability of and opportunities for public transport; d) local car ownership levels; and e) the need to ensure an adequate provision of spaces for charging plug-in and other ultra-low emission vehicles.”